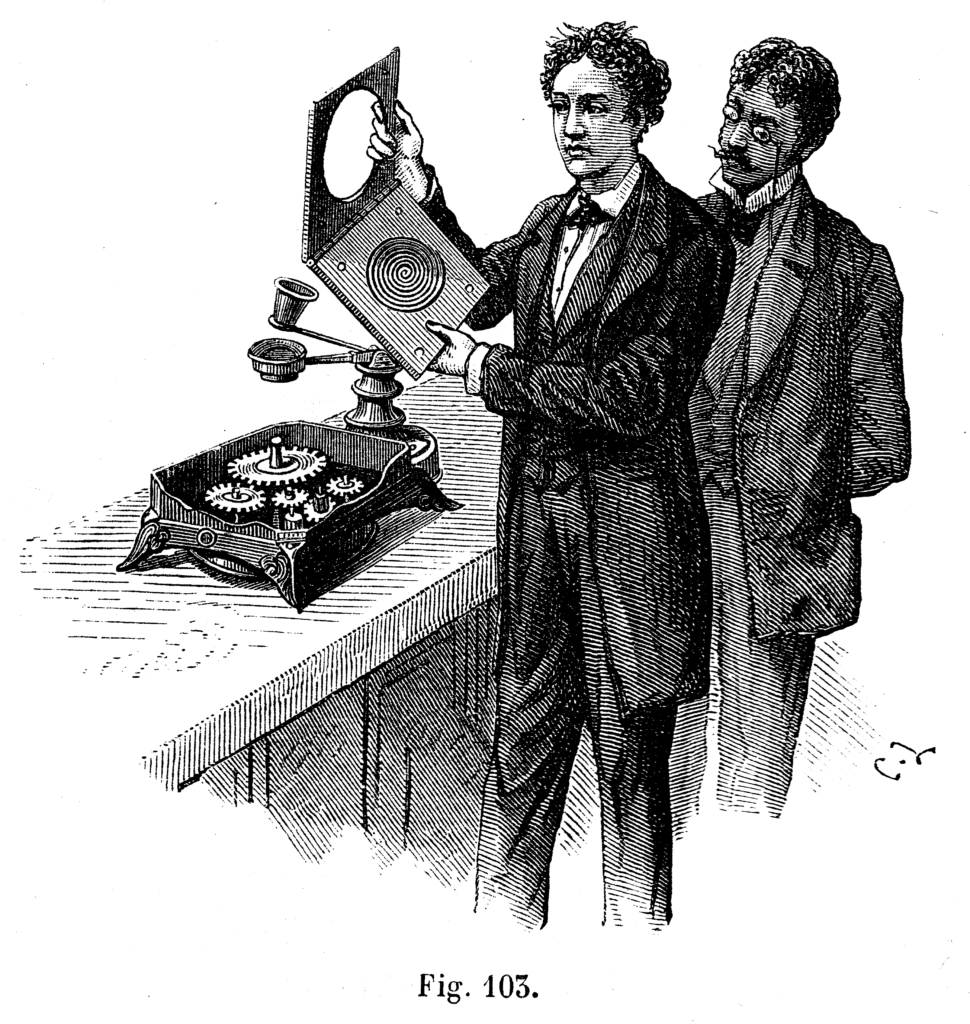

The first piece of music to ever be recorded was Mary Had A Little Lamb. According to a PBS chronology, Thomas Edison discovered a means of recording audio during some experimentation with a telegraph machine in 1877. “By the end of the year…”, Edison invents his phonograph and, “…becomes the first inventor to successfully record the human voice…” (Taintor). This was a remarkable discovery, because prior to date, all music had to be experienced in a live format. The inception of recorded audio must have flipped the contemporary music scene on its head.

Smithsonian Magazine briefly covers this transformation in an article written by Clive Thompson back in 2016. The subtitle of the article draws a very strong analogy. “Much like streaming music services today are reshaping our relationship with music, Edison’s invention redefined the entire industry…” (Thompson). According to Thompson and his research, the phonograph opened a sort of Pandora’s box. With one technological swing of the pendulum entire music genres were formed and ultimately the concept of hit singles became commonplace. Thompson continues by acknowledging the fact that, due to some technological restrictions, the concept of a song began to shift towards the two to three minute range, a stark contrast from previous conceptions of music. In the Smithsonian article, Thompson quotes Mark Katz, stating that, “The three minute pop song is basically an invention of the phonograph” (Thompson). In addition to a shortened cadence, the concept of a perfect performance became necessary in this new world of audio recording. As we can all imagine, the whole dynamic of recording music must have been a great leap for artists who were accustomed to live audiences, void of the meticulous nature of achieving a perfect take under sterile conditions. It was during this transformation that we began to see a separation between stage performers and studio musicians. “…the phonograph rewarded a new type of musical talent. You didn’t need to be the most charismatic or passionate performer onstage…but you did need to be able to regularly pull off a clean take” (Thompson).

Only a decade after the invention of the phonograph, inventor Emile Berliner patented a device called the gramophone. Instead of cylinders, the gramophone employed discs, which made the duplication process much easier, thus unlocking the power of mass production. Another difference between the phonograph and the gramophone was the ability to both record and playback audio. Edison’s device could do both, however, the gramophone was intended to be a listening device only. With this, Berliner began manufacturing and marketing, not only the gramophone, but also the records themselves (Bowie).

As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth, the materials and processes by which records were produced and distributed became much more refined and efficient. This opened up a cultural shift towards “automatic music”, and the business that surrounded this movement began to present conflicts between artists, publishers, and manufacturers. This turmoil led to modifications to the copyright laws that governed this new form of media (Taintor). Still yet, “Records weren’t terribly profitable for artists at first. Indeed musicians were often egregiously ripped off–particularly black ones” (Thompson).

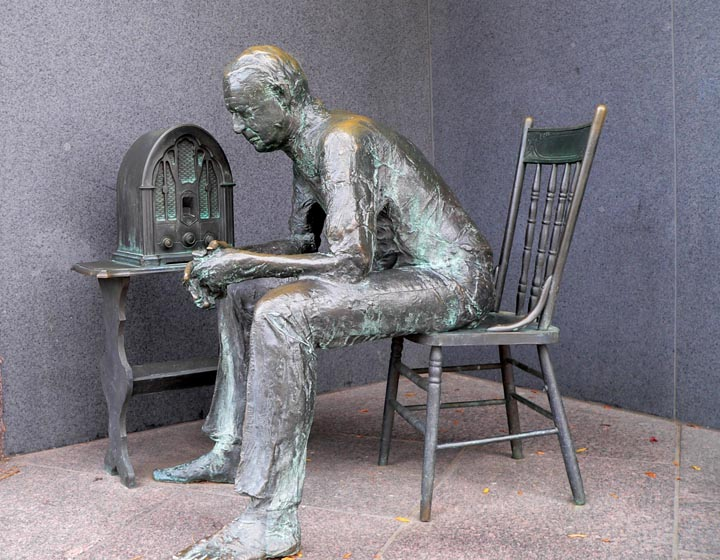

It was during the 1920’s, that radio was introduced to the equation. And as radio’s signals grew broader and broader, and their sound became more robust, the sales of physical records began to dwindle. This forced record companies to innovate once again, thus leading to the electrification, and amplification of record players. At this time both radio and record producers made significant innovations to the sonic qualities of their products. With all of this innovation, another type of innovation would need to occur on the legal front. “By law, radio was allowed to buy a record and play it on the air without paying the label or artist a penny…It would take decades of fights to establish copyright rules that required radio to pay up” (Thompson).

By 1943, the materials used in the record manufacturing process transitioned from the brittle shellac to the more durable PVC, also known as vinyl. Thus the era of vinyl records was upon us. Between the late 1940s and early 1960’s vinyl was king. But it didn’t take long for the cassette tape and 8-track to begin to make a foothold in the music industry. By 1966 all three formats were competing for listener’s preference. But, just as the radical 80s began, Sony and Phillips had combined forces to introduce a new form of media to replace all that had stood before. Introducing the Compact Disc, otherwise known as the CD. With this advanced form of audio manufacturing, the music industry flew to heights never before seen. “Within three years of the CD’s arrival in the marketplace, the electronics industry sells one million CD players” (Taintor). Note: while all of this is going on in the cultural forefront, music law is also being drafted, modified, and drafted again in the background. We now have an extremely convoluted system of copyright laws by which all parties involved in the production of recordings are governed. I will cover all of this in detail in a future blog!

Now, you might be asking, why the history lesson Liam? Well, firstly I wanted to pay homage to those who have paved the way for music as we know it. But, really the biggest reason I took you on this little trek back in time is to show you that technology and music are locked in an endless dance. Innovators innovate and create interesting tools for artists to take and innovate music. We will always be tethered to technology. It will bring us reasons to rejoice, and it will cause complications. Today’s music industry is not so different from that of the past. It is just people affecting technology, technology affecting music, music affecting people, and in turn everything else has to try and keep up. Most importantly, as independent artists (often fragile and struggling) we must keep our heads up. We must not let the noise keep us from producing beauty in the world. Let the innovators innovate, let the lawyers litigate, and let the listeners find their next favorite artist by any means necessary. All we have to do is keep creating and adapting to the world around us.

Finally, having brought us all the way up to the 80’s I feel that we have covered the early history of recorded audio. In the next few blog entries, I will begin to zoom into the modern nature of recorded audio, beginning with the introduction of the notorious MTV.

The next five blog entries in the series will be as follows:

- How The MTV Generation Changed The World

- The Early Days of Internet & Music Business

- TikTok & The Modern Music Industry

- Building A Brand As An Independent Artist

- Building An E-Commerce Website

_____________________________________________

Sources: